Although not for everyone from either a time or inclination perspective, one of the benefits of roasting coffee at home can also be it’s simplicity. True, there are many variables to consider (and hopefully control), however, if a few core principles are followed, it is certainly a process achievable to many.

In saying this, I mean no disrespect to the many professional specialty roasters out there. My point is simply this: for the home roaster, there are a few key inherent markers which occur when roasting, providing the ability to roast by “sight and sound” (as opposed to computerised tracking), without the necessity for complicated equipment. If you have a suitable means of applying enough heat to green beans, they will crack, you pull them out some time after that, and assuming this is done within a reasonable time, you end up with drinkable brew.

I have previously written about my home roasting set up, which although needs updating in a new post, is beyond the scope of what I wish to talk about here. The remainder of this post will look at one element of roasting which I have recently read about, and decided to apply myself: the development-time ratio.

Development-time ratio

One aspect of my roasting I have always tried hard to achieve is some level of consistency between batches. I was therefore particularly interested to read a guest comment on the Cropster blog by Scott Rao, who is highly regarded in the coffee industry, and has published numerous books on many aspects of coffee preparation, and most recently, roasting.

From the post:

Roasters have traditionally referred to the time from the onset of first crack until the end of a roast as “development time.” Lengthening development time to mute acidity or increase development is a common practice, especially when roasting coffee intended for espresso. However, adjusting development time without considering it in the context of the entire roast profile often destroys sweetness and creates “baked” flavors.

Rao goes on to say:

After collecting roast data of over 25,000 batches over 20 years, I noticed a pattern among the very best batches: in all of them, first crack began at between 75%–80% of total roast time. Alternatively, development time was always between 20%–25% of total roast time.

I recommend reading the original post, which also demonstrates the concept graphically with a typical roast profile.

Upon reading the article, it became clear the development-time ratio might provide a means of achieving the level of consistency I had been aiming for, or at the very least, give some indication my roasting criteria approximate some accepted parameters.

Application to my home roasting

Reading Rao’s post may at first seem to refute my point that home coffee roasting can be a simple process, however I am not suggesting we all need to rush for our calculators either. I would also note the above percentages are saying the same thing, so if you have the inclination to look at your own data, there is no need to calculate both.

In searching for some element of consistency in my roast batches, I have typically been a little uncertain around exactly which variables were the most important. Total roast time, time to first crack, development time, or a combination?

The principle of development-time ratio provides a consistent approach to every roast batch, notwithstanding changes in other variables. It requires no additional equipment, nor recording or measurement beyond the data I currently have in a log of my previous roasts.

My historical roast data

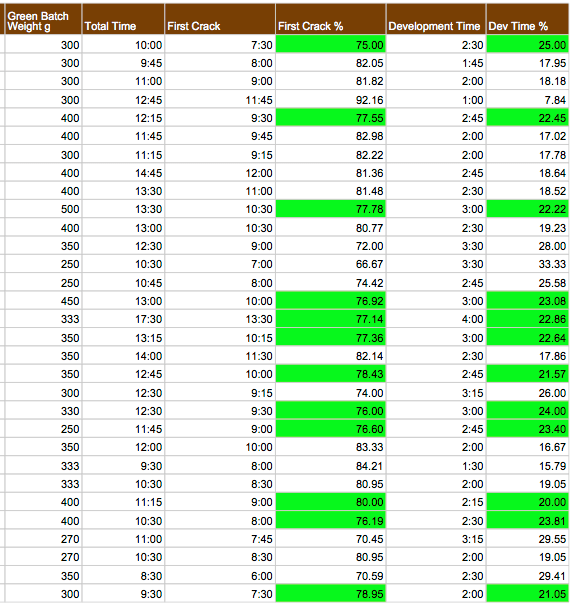

Given I have recorded sufficient data about my past roasts to assess the development-time ratio retrospectively, with the assistance of a spreadsheet, I proceeded to analyse 30 of my most recent roast batches. My initial thinking was along the lines of “these roasts will mostly fall within the 20–25% parameter”.

The result could not have been more different, and highlight the inherent flaw in assumption. Of those 30 roasts, only 11 fit Rao’s recommendation for a development-time ratio of 20–25% of total roast time (range 9.8 – 33.3%). Although the average was 21.6%, this is not particularly relevant when we are considering individual batches. A couple of things to point out here. One, I am an amateur remember! Secondly, further 17 batches were within a band of + or –5% (that is either 15–20% or 25–30%), and a number of these were pretty close to the 20 or 25% cut-off.

You will note from the data these figures are based on varying batch sizes, with considerable variation in overall roast time. As I roast outdoors with an open “drum”, I have found variation exists due to ambient temperature, time of day and the cumulative heat of the drum with successive roasts.

As expected, considerable variability in the cup was evident in relation to differing origin, processing method, roast level and brewing technique. Naturally, some were better than others, and I have not had the opportunity to compare the development-time ratio findings with my tasting notes on the particular coffees in this sample. I do not plan to spend a significant amount of time on this, as any valid results would rely on assessing the same coffee roasted in separate batches, standardising the variables from the previous paragraph. I doubt I have any current data fitting this criteria.

I have included a snapshot of the data below. As you can see, it contains both time of first crack as a percentage of total roast time, and development time as a percentage of total roast time. As I have noted above, there is no need to measure both, however for completeness I have included them here. Roasts falling within the criteria (by either measure) are shaded green.

Where to next?

There are probably a few answers to this question, the first being further reading, with Scott Rao’s The Coffee Roasters Companion high on my list. Although a good deal of the content may relate to far more sophisticated setups than mine, I find the science behind coffee roasting quite a fascinating topic. A review of the book can be found on James Hoffmann’s blog.

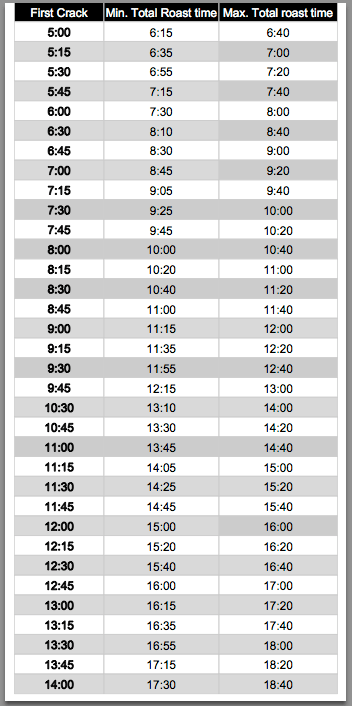

I thought I would also use the development-time ratio to standardise the total roast time in future batches, and determine whether this influences the overall quality of my roasting, and ultimately, drinking. Yet another spreadsheet here, this time to avoid the need for any complicated maths during the critical part of a roast (a printout of which is fixed firmly inside my roast record notebook).

The table below uses time to first crack (column 1), to produce the range of minimum (column 2), and maximum (column 3) roast times required to fall within Rao’s criteria for the ideal development-time ratio.

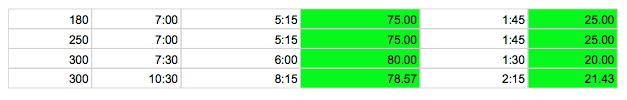

Finally, the weekend’s roast data utilising the above prediction chart (Table 2) to cease the roast based on desired development-time ratio:

Conclusion

Although this post is a little more lengthy than originally planned, the development-time ratio is a concept well worth exploring. In finding additional ways to assess, influence and standardise my roasting parameters, my skills in this area can only improve.

In the end, the proof will be in the cup, which I am looking forward to testing out.

Follow @petedenison

Nice post mate. I too am going down a similar path to you it seems, in regards to home roasting and tweaking my roasts to give better results in the cup!

LikeLike

Thanks Nick. Most roasts end up pretty enjoyable, though it’s always fun to try and improve them!

LikeLike

Pingback: Yemen Mokha Ismaili – Musings on ROR (rate of rise) | Making…Coffee and Other Stuff

You are a champion! The chart you made is exactly what I was looking for to print out and have with me while roasting. Thanks

LikeLike

That’s great Steve. I still use it when I roast – hope it helps!

Cheers.

LikeLike

Hallo! Nice post. Have you read any info about what is optimum time to get over first crack (i have read somewhere, that FC should last no longer than 2min), so it’s not considered as streched?

LikeLike

Hi Ingus,

In relation to the length of first crack, I don’t have a specific source to refer you to, however I find most of my better roasts occur when first crack begins and ends within about a 1:30 – 2:00 time period. I’m assuming the closer together the crack occurs for all of the beans the more evenly roasted the batch will be, and stalling the roast tends to bake the beans to some degree I believe. So in my experience (as an amateur home roaster anyway) I would tend to agree with what you have heard on this particular aspect.

Thanks for stopping by and reading the post!

Pete

LikeLike

Thank’s for answer 😉 I’m also home roaster amateur and I use hot gun – dog bowl method 🙂

LikeLike